January 8, 2026

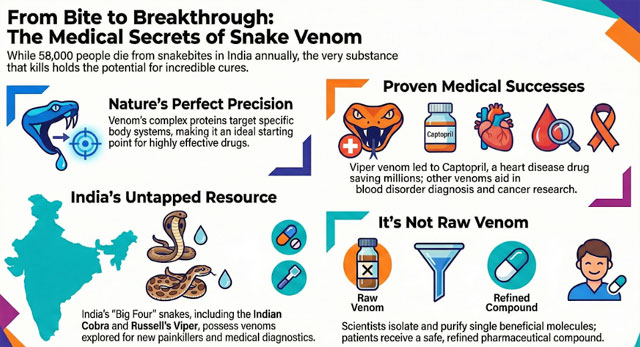

When I first learned that more than 58,000 people die every year in India due to snakebites, my immediate reaction was fear. For centuries, snakes have been associated with danger and death. Yet modern science has revealed a surprising truth: the same venom that kills can also save lives. Nobel laureate Dr David Julius, whose research transformed pain biology, has observed that “venoms are incredibly powerful tools for understanding biology because they act with extraordinary precision.” This precision is exactly what makes venom so valuable to modern medicine. Snake venom, once regarded only as a lethal poison, is now helping scientists develop important drugs. What appears to be a contradiction is, in reality, one of the most compelling stories in biomedical science.

The Medicine Hidden in Venom

This story begins not in India, but in Brazil. In the 1960s, Brazilian researcher Dr Sérgio Ferreira discovered that compounds in the venom of the Brazilian pit viper could regulate blood pressure. His work eventually led to the development of captopril, one of the world’s first and most widely prescribed drugs for hypertension and heart disease. Reflecting on such discoveries, Nobel Prize–winning pharmacologist Sir John Vane famously remarked that “nature has often been the best chemist.” Venoms, refined through millions of years of evolution, exemplify this idea. This was not a one-time breakthrough. Venom from the saw-scaled viper is now used in laboratories to diagnose blood-clotting disorders. Compounds derived from black mamba venom are being studied as potential painkillers that may avoid the addictive risks of opioids. Copperhead venom has shown promise in cancer research by interfering with the spread of tumour cells.

India’s Snakes and Their Scientific Promise

India is home to some of the world’s most medically significant snakes, including the well-known “Big Four”: the Indian cobra, Russell’s viper, the saw-scaled viper, and the common krait. While these species are responsible for many snakebite deaths, their venoms also possess immense scientific value. Leading toxinologist Professor Bryan Fry has highlighted that “venoms have evolved to be exquisitely selective, making them ideal starting points for drug development.” This selectivity explains why venom-based research continues to attract global scientific attention. Indian cobra venom is being explored for applications in pain management and cancer therapy, while Russell’s viper venom is already used in diagnostic tests for blood coagulation disorders. These examples reveal an important reality: India’s snakes are not only a public health challenge, but also a largely untapped biomedical resource.

Why Venom Works So Well

Snake venom is not a single toxin. It is a complex mixture of proteins and enzymes, each designed to target specific physiological systems such as nerves, blood, or cells. This natural targeting ability is exactly what modern drug discovery strives to achieve. Importantly, venom itself is never used directly as medicine. Scientists isolate beneficial molecules, modify them to ensure safety, and test them rigorously over many years. What reaches patients is a refined pharmaceutical compound—not venom.

The Road Ahead

India has more than 300 snake species, many of which remain poorly studied. Institutions such as the Institute of Bioinformatics and Applied Biotechnology in Bengaluru and the Irula Snake Catchers Cooperative Society in Tamil Nadu are supporting ethical venom research while promoting conservation and public safety. Transforming venom into medicine is slow and uncertain, and many promising compounds fail along the way. Yet when research succeeds, the impact can be extraordinary. Captopril alone has saved millions of lives worldwide. India faces a severe snakebite crisis, but it also holds the potential for future cures. When understood and used responsibly, nature’s deadliest substances can become powerful tools for healing.